Tuesday, November 30, 2004

Chance meeting leads to author's flowering

I could very easily have brushed off Sam Stahl, a North Port resident who recently published "Three Satisfictions," a collection of novellas.

Stahl, an older, balding man who wears glasses and favors long, collarless white shirts, stopped me one day at the door of the North Port Sun.

“Hey, aren't you the book columnist fellow?” he asked.

Journalists know that the results aren’t usually pleasant when a passerby identifies them. From political polemics to personal put-downs, the buttonholer is almost guaranteed to have some sort of invective to deliver.

But Stahl appeared to be a nice enough guy. Besides, I don't brush people off. So I responded in the affirmative. It turned out that Stahl was a frustrated author, who several decades ago had written a series of novellas. The stories were creative and reflective retellings of experiences that ranged from partying with expatriates in Spain to arguing religion with true believers in a New York skyscraper.

Stahl came of age during the hedonistic days of the late 50s and 60s, when the consequences of our actions were still far beyond the horizon. I‘m relatively younger (relative is supremely operative here), yet I recognized the characters in his novels as candidates for Frank Sinatra's Rat Pack, or the cool, amoral men and women portrayed in movies of the era such as "La Dolce Vita" or “Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.”

Those characters, like Stahl's, seldom considered consequences as they careered through life in search of the next piece of soft flesh or stiff gin and tonic--"shaken, not stirred."

Stahl has a rough style that's initially off-putting. As I first read through his manuscript, I applied a pencil liberally until it hit me: Sam Stahl writes the way people think, in staccato bursts of disconnected ideas punctuated by periods of coherent introspection. Punctuation is the key here. Stahl's sentences are sometimes grammatically incorrect, punctuated or broken by a character's pause for breath or Stahl's tight negotiations of a plot's sinuous curves.

I realized that I was trampling Stahl's gritty voice by attempting to make it conform to common usage. When read as a sort of dialect, his dialogue and narration spring to life, accurately reflecting the mood changes of the characters with the alacrity of a sharp crew tacking at the slightest breeze.

The characters' crisp cadence is matched by the speed with which Stahl manipulates them, driving them from scene to scene with a brio reminiscent of those long-gone "Go-Go" days.

Those thoughts informed my words the next time I saw Stahl. His material was dated, I said, but in a way that would resonate with anyone from that era. Stahl writes of a time long gone, an era in which skirts grew shorter as the war in Vietnam grew longer. Today, questioning authority comes as readily to the body public as sneezing. But in those days many conventions, from those of grammar to those of greater import, such as those governing morality or politics, were giving way as authority was being questioned in ways that still bear consequences almost half a century later.

I told him his work was pretty good, and that he should get published. But Stahl is in his 80s. I told him he'd probably be long gone before he was able to make it through the rounds of New York agents and publishing houses in search of a contract.

Instead, I suggested, why not self-publish? At the time, I had yet to plunge myself into the world of small publishing. But I had written about it, and given enough advice about it, to know where to guide Stahl.

I referred him to Carol Mahler, of the Peace River Center for Writers, and Jim and Linda Salisbury of Tabby House Press.

Months later, Stahl came into the office to present me with a copy of "Three Satisfictions," a collection of three novellas.

He writes the way men and women wrote about men and women, before political correctness rendered much of what truly occupies the minds of the two sexes not permissible for publication.

His work brings to mind Kate Chopin or Ernest Hemingway, two writers who pushed the bounds of convention in accurately relating how men and women thought about themselves and those around them. His commentaries on the perpetual encounters between Venus and Mars may shock some, but so does a straight dose of honesty. Anyone who invests time in this work will harvest an honest appreciation of what makes our sexes chart such disparate yet converging courses.

Here's an example, as Touch, the heel of "Corridas in the Rain," the first of three novellas in Stahl's book, opens negotiations with some lusty prey:

"Entering empty Bar Central, there she was, Liz Laughton, seated all by herself, showing in her eyes, as from some private momentum or booze, how glad she was to see him.

"And how are things with my Touchiepooh, tonight?"

"They just hugely improved."

"Touch, look at you. I've never seen you so high."

"Or you so lovely."

"You were missing at the Necker thing."

"You didn't take me."

"Johnny and Trilby were there," she said. "They're such a nice couple. He busts his buttons trying not to show it. Oh, Touch, don't begrudge Johnny something nice."

"There are compensations," he said.

"Yes?"

"The wife of one of the finest men I know."

Her look then, her booze thing, had slipped, being suddenly coy.

"Would you have me different than what I am?" he said.

"My favorite big bear."

"Let's do a private investigation. My place?"

Touch is as smooth as butter. And just as substantial.

Stahl's characters, in his fine, rough work, seldom come to grips with the consequences of their actions. And, if Stahl had not determined to follow his destiny, albeit several decades removed, those same characters would have fought and loved in obscurity.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com.

Stahl, an older, balding man who wears glasses and favors long, collarless white shirts, stopped me one day at the door of the North Port Sun.

“Hey, aren't you the book columnist fellow?” he asked.

Journalists know that the results aren’t usually pleasant when a passerby identifies them. From political polemics to personal put-downs, the buttonholer is almost guaranteed to have some sort of invective to deliver.

But Stahl appeared to be a nice enough guy. Besides, I don't brush people off. So I responded in the affirmative. It turned out that Stahl was a frustrated author, who several decades ago had written a series of novellas. The stories were creative and reflective retellings of experiences that ranged from partying with expatriates in Spain to arguing religion with true believers in a New York skyscraper.

Stahl came of age during the hedonistic days of the late 50s and 60s, when the consequences of our actions were still far beyond the horizon. I‘m relatively younger (relative is supremely operative here), yet I recognized the characters in his novels as candidates for Frank Sinatra's Rat Pack, or the cool, amoral men and women portrayed in movies of the era such as "La Dolce Vita" or “Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.”

Those characters, like Stahl's, seldom considered consequences as they careered through life in search of the next piece of soft flesh or stiff gin and tonic--"shaken, not stirred."

Stahl has a rough style that's initially off-putting. As I first read through his manuscript, I applied a pencil liberally until it hit me: Sam Stahl writes the way people think, in staccato bursts of disconnected ideas punctuated by periods of coherent introspection. Punctuation is the key here. Stahl's sentences are sometimes grammatically incorrect, punctuated or broken by a character's pause for breath or Stahl's tight negotiations of a plot's sinuous curves.

I realized that I was trampling Stahl's gritty voice by attempting to make it conform to common usage. When read as a sort of dialect, his dialogue and narration spring to life, accurately reflecting the mood changes of the characters with the alacrity of a sharp crew tacking at the slightest breeze.

The characters' crisp cadence is matched by the speed with which Stahl manipulates them, driving them from scene to scene with a brio reminiscent of those long-gone "Go-Go" days.

Those thoughts informed my words the next time I saw Stahl. His material was dated, I said, but in a way that would resonate with anyone from that era. Stahl writes of a time long gone, an era in which skirts grew shorter as the war in Vietnam grew longer. Today, questioning authority comes as readily to the body public as sneezing. But in those days many conventions, from those of grammar to those of greater import, such as those governing morality or politics, were giving way as authority was being questioned in ways that still bear consequences almost half a century later.

I told him his work was pretty good, and that he should get published. But Stahl is in his 80s. I told him he'd probably be long gone before he was able to make it through the rounds of New York agents and publishing houses in search of a contract.

Instead, I suggested, why not self-publish? At the time, I had yet to plunge myself into the world of small publishing. But I had written about it, and given enough advice about it, to know where to guide Stahl.

I referred him to Carol Mahler, of the Peace River Center for Writers, and Jim and Linda Salisbury of Tabby House Press.

Months later, Stahl came into the office to present me with a copy of "Three Satisfictions," a collection of three novellas.

He writes the way men and women wrote about men and women, before political correctness rendered much of what truly occupies the minds of the two sexes not permissible for publication.

His work brings to mind Kate Chopin or Ernest Hemingway, two writers who pushed the bounds of convention in accurately relating how men and women thought about themselves and those around them. His commentaries on the perpetual encounters between Venus and Mars may shock some, but so does a straight dose of honesty. Anyone who invests time in this work will harvest an honest appreciation of what makes our sexes chart such disparate yet converging courses.

Here's an example, as Touch, the heel of "Corridas in the Rain," the first of three novellas in Stahl's book, opens negotiations with some lusty prey:

"Entering empty Bar Central, there she was, Liz Laughton, seated all by herself, showing in her eyes, as from some private momentum or booze, how glad she was to see him.

"And how are things with my Touchiepooh, tonight?"

"They just hugely improved."

"Touch, look at you. I've never seen you so high."

"Or you so lovely."

"You were missing at the Necker thing."

"You didn't take me."

"Johnny and Trilby were there," she said. "They're such a nice couple. He busts his buttons trying not to show it. Oh, Touch, don't begrudge Johnny something nice."

"There are compensations," he said.

"Yes?"

"The wife of one of the finest men I know."

Her look then, her booze thing, had slipped, being suddenly coy.

"Would you have me different than what I am?" he said.

"My favorite big bear."

"Let's do a private investigation. My place?"

Touch is as smooth as butter. And just as substantial.

Stahl's characters, in his fine, rough work, seldom come to grips with the consequences of their actions. And, if Stahl had not determined to follow his destiny, albeit several decades removed, those same characters would have fought and loved in obscurity.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com.

Sunday, November 28, 2004

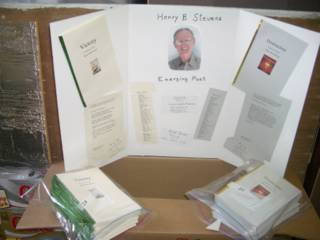

Florida Writers's Association Royal Palm Awards 2004, Henry Burt Stevens, 1st place poetry. The video is the FWA year in review, and my poem "Victory" was the indroductory piece. I'm very thankful.

Sunday, November 21, 2004

Book Review by James Abraham

How home sweet home lost its sweetness

The next time you have to climb into your car to go get a loaf of bread as you wonder why your housing development lacks local schools, hospitals or other such amenities, do this: Slow down, take a deep breath, and read "Building Suburbia," ($26, Random House) by Dolores Hayden.

Her book, subtitled "Greenfields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000," offers the best single-volume guide to how the road to a quiet place in the country became a crowded freeway to suburbia.

How exciting can a discourse on urban planning be? Well, read the book and see how Hayden plows new ground in discussing the post-war housing boom.

"The planning of these postwar suburbs was often presented in the press as hasty, driven by the patriotic need to meet the demand for housing created by the khaki-clad, beribboned heroes returned from the Battle of the Bulge...The press attributed problems in suburb design to rushed planning, but this was not the case. Backroom politics of the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s had shaped postwar housing and urban design. There was no haste at all in the twenty years of lobbying for federal support of private-market, single-family housing development. The postwar suburbs were constructed at great speed, but they were deliberately planned to maximize consumption of mass-produced goods and minimize the responsibility of the developers to create public space and public services."

We were robbed, both as homeowners and as tax-payers, by guys out to make a buck on our dreams of home ownership.

Hayden writes of the fabled Levitts of Long Island's Levittown, stripping back the layer of myths about the father and two sons who built 17,000 homes during the post-war housing boom.

"Levitt and Sons often boasted that they "set aside" land for schools to both towns, but according to the NYU report, they paid for nothing and built nothin," writes Hayden. "Towns had to assess the taxpayers in special districts to pay for the land costs as well as school buildings, school operations and public libraries. "

Residents and governments were left holding the bag as the Levitts shucked off the burden of infrastructure on government, thus stranding thousands of homeowners miles from schools or shops. In the original Levittown, writes Hayden, the builders left the residents with cesspools instead of sewers. Guess who paid to create a sanitary disposal system?

Services were soon outstripped in the counties and towns whose borders made them responsible for the Levitts' metastasizing homes. Taxes rose as residents found themselves paying to extend trash, police, fire and rescue services to thousands of new homes and newer residents annually.

What went wrong? What turned the American dream of a nice, quiet home in the country into this nightmare of mega-developments and endangered green fields?

Unchecked capitalism, says Hayden. She offers the reader a historical view of the first suburbs, areas of borderlands where city dwellers with the wherewithal would repair to build nascent suburbs. From the religious sects of the nineteenth century such as the Shakers to the exclusive gated communities of that era's wealthy, the stories of such communities inform Hayden's thesis that the desire for peace, quiet and safety was compromised early on.

A destination close to commerce, schools and urban services but far from the madding crowd has always been somewhat illusory, Hayden writes. Sure, if one had enough money one could do what was done in Baltimore's Roland Park or New York's Tuxedo Park, where wealthy men built private, gated suburbs close the city.

But all too often, as Hayden writes, what resulted was either an elitist shell of a "good neighborhood" or an end to the dream as the surrounding urban area expanded to engulf the Eden of seclusion.

One can see examples of both those phenomena in our state. In North Port, residents who years ago thought they were living on the edge of that fast-growing town, for example, south of the Holiday Park area, now find themselves swallowed up in the burgeoning community's south-southeast growth pattern.

And Abacoa, a glittering "New Urbanism" community near Jupiter designed to hearken back to old-fashioned neighborhoods -- with a mix of diversity -- is instead an enclave of wealth, as the cost of realizing the development's goal has placed its units far beyond the capacity of the average resident.

Hayden looks beyond the confines of housing to examine the other components of the built environment necessary for a community's sustainable growth and how they contributed to the erosion of peace and comfort suburban living was expected to foster.

She tells how tax breaks granted by Republican administrations encouraged big box store and strip mall owners to build cheaply, then profit by pulling out and leaving a community with a huge abandoned piece of real estate. The developers made money by employing low-skilled, non-union labor, thus driving down wages in the area. Families forced to drive long distances helped every component of the auto industry and its ancillary industries, from Fords to fast-food joints, grow rich at the expense of center cities starved by the outflux of industry and taxpayers bound for the suburbs.

Left behind were the worst jobs, the worst kind of people (at least in many a suburban emigre's eyes) and eventually the worst buildings.

Hayden takes such a scenario to its logical high-tech conclusion, as families cocoon in smart houses to telecommute, shop on-line for goods and services, and otherwsie sustain themselves.

Walls would be replaced with computer-generated images of city streets, concert halls, daisy fields or whatever visual stimulation soothed and satisfied the smart house owner.

Of course, the rest of us unable ro afford a smart house would be still out there in that brave cool world, sucking up auto fumes and wondering why we have to shoulder such a large burden to maintain basic municipal services.

But it doesn't have to end that way. Hayden offers concrete suggestions for true urban renewal. Concepts such as historic preservation, urban service boundaries, or energy conservation are as old as traffic jams. But Hayden brings new insight and intelligent historical context to her advocacy of those elements of good comprehensive growth plans.

Better yet, she wisely suggests that only a change in political will would effect a change in the way houses are developed and greenlands destroyed. After writing a road map of the major legislative actions that concretized our suburban ways, Hayden says Congress and governments must now clean up a system that favors houses as units rather than as parts of a community whole. Only informed and intelligent citizen pressure can bring about such a change, she says.

Hayden, a Yale University professor, has written often and well about the sad dynamics of our cities and suburbs. It's to the professor's credit that, instead of playing Cassandra and then skedaddling for the 'burbs, she argues cogently for some practical solutions that could lead us back to the road of our national dream.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com.

The next time you have to climb into your car to go get a loaf of bread as you wonder why your housing development lacks local schools, hospitals or other such amenities, do this: Slow down, take a deep breath, and read "Building Suburbia," ($26, Random House) by Dolores Hayden.

Her book, subtitled "Greenfields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000," offers the best single-volume guide to how the road to a quiet place in the country became a crowded freeway to suburbia.

How exciting can a discourse on urban planning be? Well, read the book and see how Hayden plows new ground in discussing the post-war housing boom.

"The planning of these postwar suburbs was often presented in the press as hasty, driven by the patriotic need to meet the demand for housing created by the khaki-clad, beribboned heroes returned from the Battle of the Bulge...The press attributed problems in suburb design to rushed planning, but this was not the case. Backroom politics of the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s had shaped postwar housing and urban design. There was no haste at all in the twenty years of lobbying for federal support of private-market, single-family housing development. The postwar suburbs were constructed at great speed, but they were deliberately planned to maximize consumption of mass-produced goods and minimize the responsibility of the developers to create public space and public services."

We were robbed, both as homeowners and as tax-payers, by guys out to make a buck on our dreams of home ownership.

Hayden writes of the fabled Levitts of Long Island's Levittown, stripping back the layer of myths about the father and two sons who built 17,000 homes during the post-war housing boom.

"Levitt and Sons often boasted that they "set aside" land for schools to both towns, but according to the NYU report, they paid for nothing and built nothin," writes Hayden. "Towns had to assess the taxpayers in special districts to pay for the land costs as well as school buildings, school operations and public libraries. "

Residents and governments were left holding the bag as the Levitts shucked off the burden of infrastructure on government, thus stranding thousands of homeowners miles from schools or shops. In the original Levittown, writes Hayden, the builders left the residents with cesspools instead of sewers. Guess who paid to create a sanitary disposal system?

Services were soon outstripped in the counties and towns whose borders made them responsible for the Levitts' metastasizing homes. Taxes rose as residents found themselves paying to extend trash, police, fire and rescue services to thousands of new homes and newer residents annually.

What went wrong? What turned the American dream of a nice, quiet home in the country into this nightmare of mega-developments and endangered green fields?

Unchecked capitalism, says Hayden. She offers the reader a historical view of the first suburbs, areas of borderlands where city dwellers with the wherewithal would repair to build nascent suburbs. From the religious sects of the nineteenth century such as the Shakers to the exclusive gated communities of that era's wealthy, the stories of such communities inform Hayden's thesis that the desire for peace, quiet and safety was compromised early on.

A destination close to commerce, schools and urban services but far from the madding crowd has always been somewhat illusory, Hayden writes. Sure, if one had enough money one could do what was done in Baltimore's Roland Park or New York's Tuxedo Park, where wealthy men built private, gated suburbs close the city.

But all too often, as Hayden writes, what resulted was either an elitist shell of a "good neighborhood" or an end to the dream as the surrounding urban area expanded to engulf the Eden of seclusion.

One can see examples of both those phenomena in our state. In North Port, residents who years ago thought they were living on the edge of that fast-growing town, for example, south of the Holiday Park area, now find themselves swallowed up in the burgeoning community's south-southeast growth pattern.

And Abacoa, a glittering "New Urbanism" community near Jupiter designed to hearken back to old-fashioned neighborhoods -- with a mix of diversity -- is instead an enclave of wealth, as the cost of realizing the development's goal has placed its units far beyond the capacity of the average resident.

Hayden looks beyond the confines of housing to examine the other components of the built environment necessary for a community's sustainable growth and how they contributed to the erosion of peace and comfort suburban living was expected to foster.

She tells how tax breaks granted by Republican administrations encouraged big box store and strip mall owners to build cheaply, then profit by pulling out and leaving a community with a huge abandoned piece of real estate. The developers made money by employing low-skilled, non-union labor, thus driving down wages in the area. Families forced to drive long distances helped every component of the auto industry and its ancillary industries, from Fords to fast-food joints, grow rich at the expense of center cities starved by the outflux of industry and taxpayers bound for the suburbs.

Left behind were the worst jobs, the worst kind of people (at least in many a suburban emigre's eyes) and eventually the worst buildings.

Hayden takes such a scenario to its logical high-tech conclusion, as families cocoon in smart houses to telecommute, shop on-line for goods and services, and otherwsie sustain themselves.

Walls would be replaced with computer-generated images of city streets, concert halls, daisy fields or whatever visual stimulation soothed and satisfied the smart house owner.

Of course, the rest of us unable ro afford a smart house would be still out there in that brave cool world, sucking up auto fumes and wondering why we have to shoulder such a large burden to maintain basic municipal services.

But it doesn't have to end that way. Hayden offers concrete suggestions for true urban renewal. Concepts such as historic preservation, urban service boundaries, or energy conservation are as old as traffic jams. But Hayden brings new insight and intelligent historical context to her advocacy of those elements of good comprehensive growth plans.

Better yet, she wisely suggests that only a change in political will would effect a change in the way houses are developed and greenlands destroyed. After writing a road map of the major legislative actions that concretized our suburban ways, Hayden says Congress and governments must now clean up a system that favors houses as units rather than as parts of a community whole. Only informed and intelligent citizen pressure can bring about such a change, she says.

Hayden, a Yale University professor, has written often and well about the sad dynamics of our cities and suburbs. It's to the professor's credit that, instead of playing Cassandra and then skedaddling for the 'burbs, she argues cogently for some practical solutions that could lead us back to the road of our national dream.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com.

Saturday, November 20, 2004

Flag by Henry B Stevens

Not moving, not dancing

lying very still

now a coverlet

a decoration

for remains forever static.

The starred blue square

marks the head

although we do not know

or ask if there is a head inside.

The red white stripes

point to the feet

as in patrol, platoon

squad and squadron.

Do not look or note

or photograph these flags

covering metal boxes

it's unpatriotic.

Do not recite the names

of what the remains were called

as it aids the enemy

is an intrusion on family grief.

Do explain to the children

especially the very young ones

why flags are gleefully everywhere

when starting the war.

But now we do not look at

or think about

flags on

metal boxes.

Reprinted from "Victory" a chapbook of poetry by Henry Burt Stevens

Avialable from http://vicopress.com click on BOOKS

lying very still

now a coverlet

a decoration

for remains forever static.

The starred blue square

marks the head

although we do not know

or ask if there is a head inside.

The red white stripes

point to the feet

as in patrol, platoon

squad and squadron.

Do not look or note

or photograph these flags

covering metal boxes

it's unpatriotic.

Do not recite the names

of what the remains were called

as it aids the enemy

is an intrusion on family grief.

Do explain to the children

especially the very young ones

why flags are gleefully everywhere

when starting the war.

But now we do not look at

or think about

flags on

metal boxes.

Reprinted from "Victory" a chapbook of poetry by Henry Burt Stevens

Avialable from http://vicopress.com click on BOOKS

Wednesday, November 17, 2004

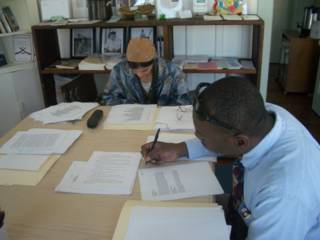

Carol Mahler, executive director of Peace River Center for Writers for the first two years. It's safe to say that many thousands of people read and write better than they used to because of Carol. Shown here at her dedication, bending over a student's work.

Peace River Center for Writers is a smoke free enviorment. However, smoking facilities are nearby. James Abraham, left, Lynn Harrell, right.

Carol Mahler, center, James Abraham, right, judging a writing contest at the Peace River Center for Writers.

James M Abraham, who writes columns and book reviews for vicopress.com Picture taken at the Peace River Center for Writers in Punta Gorda, FL.

Sunday, November 14, 2004

Interview-Jillian Foster Knight by James Abraham

Knight’s retellings bring new meaning to old myths

Jillian Foster Knight is a 27-year-old Clearwater native who writes poetry. And, if that were the end of the story, her tale would be similar to that of thousands of wannabes who write endless lines of prosy while awaiting their big break.

But Knight’s spunk has lifted her out of that cycle. She made her own big break. Years ago, after finally compiling a body of work she wanted to publish; Knight did not wait around. She taught herself bookbinding skills, and soon produced a handsome 9X6 version of retold Greek myths.

Therein lies the value of her art, that her words are framed well in volumes of gorgeous craftsmanship.

"I wanted to create something that looked like I made it," Knight said.

She's done that and more. Her volumes, "Re-Written: tales of Celtic mythology," and "Re-Written: tales of Greek mythology," are retellings of old myths imbued with Knight’s spirit.

The books themselves are singular works. They are printed on heavy paper with canvas-bound covers and stitched binding. Knight shapes the books herself, spending up to eight hours per volume crafting them with an industrial sewing machine, clamps, gluepots and other rude technologies of her.

The pages of her books are ragged, calling to mind the days when books were shipped with pages uncut, and a bibliophile’s first pleasure before reading was slicing open the pages.

"I don’t think anybody should write unless they’ve experienced life," Knight says. Those words, coming from the lips of a woman who looks like a kid, may evoke laughter because of the apparently incongruous juxtaposition of age and statement. After all, how much experience does a 27-year-old have these days, where we see thirty-somethings living at home and berating mommy because she hasn’t purchased the favorite cereal?

But Knight knows of what she speaks. She and her parents are historical reenactors, who traverse the country making and selling homemade artifacts. Knight has her own tent, and makes camp near her parents, selling her wares by day and curling up in a cot in a corner of the big white canopy at night. She lives in the high mountains and deep woods of western Appalachia, and supports herself through her books and her business of selling artifacts she makes or finds in her travels.

So, in a society in which many adults have never left the home of their birth or travel in hermetically sealed containers of steel and rubber, Knight’s life and travels have certainly afforded her the experience needed to produce her work.

That experience is evident in her work. Here’s an example:

I have become your Echo

You became all too many things

I could never compete, never even dared

You were just…

spellbound within yourself.

Everything I hoped to say

Was already spoken.

I was just your Echo.

That, of course, is from the myth of Echo and Narcissus, the story of a young nymph and her unrequited love for a most handsome fellow. Narcissus was so good-looking that he pined away while gazing at his own beauty in a reflecting pool. Echo herself pined away to nothing because Narcissus was too busy admiring himself. An old tale, but the heartache evident in Knight’s retelling speaks to that feeling of abandonment shared by any woman who sacrificed all for a man who barely knew she was there.

Just as abused women blame themselves right down to the last humiliation at the hands of their abusers, so does it appear that Echo faults herself for not being pretty enough. In a society in which women have been taught to be good victims, Echo’s sentiments still ring true.

In "After the Ganconer," from Knight’s book of Gaelic tales, she uses poetic license to reverse the traditional role of the title character’s victims. A ganconer is literally a love-talker, a handsome spirit who loves milkmaids and shepherdesses so well that they are left unsatisfied by mortal hands.

Your sweet smile.

Your honeyed words.

The way you held me

I believed I was it.

The only girl.

Your sweet talk,

But I won’t fall again.

Positions are now reversed.

Now I strip you raw

and leave you wanting,

wanting more

more of the things I will never give you.

I will never give you

What it is you need.

I gave everything once.

Maybe that poem is only a wistful dream of what should have happened, a lyric example of the telling retort or appropriate response that only comes to us when it’s too late.

Both books, while beautiful, describe the ugly aspects of interpersonal relations. If there’s a sun radiating light, there must be a moon to reflect it. Knight’s at a tender age to understand that truth, and her honesty informs her fine collection of handcrafted volumes.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com

Jillian Foster Knight is a 27-year-old Clearwater native who writes poetry. And, if that were the end of the story, her tale would be similar to that of thousands of wannabes who write endless lines of prosy while awaiting their big break.

But Knight’s spunk has lifted her out of that cycle. She made her own big break. Years ago, after finally compiling a body of work she wanted to publish; Knight did not wait around. She taught herself bookbinding skills, and soon produced a handsome 9X6 version of retold Greek myths.

Therein lies the value of her art, that her words are framed well in volumes of gorgeous craftsmanship.

"I wanted to create something that looked like I made it," Knight said.

She's done that and more. Her volumes, "Re-Written: tales of Celtic mythology," and "Re-Written: tales of Greek mythology," are retellings of old myths imbued with Knight’s spirit.

The books themselves are singular works. They are printed on heavy paper with canvas-bound covers and stitched binding. Knight shapes the books herself, spending up to eight hours per volume crafting them with an industrial sewing machine, clamps, gluepots and other rude technologies of her.

The pages of her books are ragged, calling to mind the days when books were shipped with pages uncut, and a bibliophile’s first pleasure before reading was slicing open the pages.

"I don’t think anybody should write unless they’ve experienced life," Knight says. Those words, coming from the lips of a woman who looks like a kid, may evoke laughter because of the apparently incongruous juxtaposition of age and statement. After all, how much experience does a 27-year-old have these days, where we see thirty-somethings living at home and berating mommy because she hasn’t purchased the favorite cereal?

But Knight knows of what she speaks. She and her parents are historical reenactors, who traverse the country making and selling homemade artifacts. Knight has her own tent, and makes camp near her parents, selling her wares by day and curling up in a cot in a corner of the big white canopy at night. She lives in the high mountains and deep woods of western Appalachia, and supports herself through her books and her business of selling artifacts she makes or finds in her travels.

So, in a society in which many adults have never left the home of their birth or travel in hermetically sealed containers of steel and rubber, Knight’s life and travels have certainly afforded her the experience needed to produce her work.

That experience is evident in her work. Here’s an example:

I have become your Echo

You became all too many things

I could never compete, never even dared

You were just…

spellbound within yourself.

Everything I hoped to say

Was already spoken.

I was just your Echo.

That, of course, is from the myth of Echo and Narcissus, the story of a young nymph and her unrequited love for a most handsome fellow. Narcissus was so good-looking that he pined away while gazing at his own beauty in a reflecting pool. Echo herself pined away to nothing because Narcissus was too busy admiring himself. An old tale, but the heartache evident in Knight’s retelling speaks to that feeling of abandonment shared by any woman who sacrificed all for a man who barely knew she was there.

Just as abused women blame themselves right down to the last humiliation at the hands of their abusers, so does it appear that Echo faults herself for not being pretty enough. In a society in which women have been taught to be good victims, Echo’s sentiments still ring true.

In "After the Ganconer," from Knight’s book of Gaelic tales, she uses poetic license to reverse the traditional role of the title character’s victims. A ganconer is literally a love-talker, a handsome spirit who loves milkmaids and shepherdesses so well that they are left unsatisfied by mortal hands.

Your sweet smile.

Your honeyed words.

The way you held me

I believed I was it.

The only girl.

Your sweet talk,

But I won’t fall again.

Positions are now reversed.

Now I strip you raw

and leave you wanting,

wanting more

more of the things I will never give you.

I will never give you

What it is you need.

I gave everything once.

Maybe that poem is only a wistful dream of what should have happened, a lyric example of the telling retort or appropriate response that only comes to us when it’s too late.

Both books, while beautiful, describe the ugly aspects of interpersonal relations. If there’s a sun radiating light, there must be a moon to reflect it. Knight’s at a tender age to understand that truth, and her honesty informs her fine collection of handcrafted volumes.

James M. Abraham, a syndicated book columnist, can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com

Sunday, November 07, 2004

Book Review-James M Abraham

Old-style politics makes great read

Edwin O’Connor’s "The Last Hurrah" is the fast-moving, well-textured story of the last mayoral campaign of city boss J. Frank Skeffington.

But "Hurrah," written in 1956, is a forgotten book today. More folks probably remember the movie of the same title, which starred Spencer Tracy and adhered well to the book. That’s too bad because "Hurrah" is probably the most well- developed political novel ever written. In our time it can be compared more than favorably with Joe Klein’s "Primary Colors," the popular book by a magazine writer about a rising political star from Arkansas.

"Hurrah" takes us from the political novel standard set by poet-laureate Robert Penn Warren’s gloomy "All the King’s Men" to "Colors."

But of that trinity of twentieth century American political novels, "Hurrah" is the most underrated. Here’s why, even as many celebrate or hibernate in the days following the presidential election, readers should consider picking up a copy of the book for a not-so-distant reflection of politics in an earlier time. And here’s what separates "Hurrah" from the two better-known novels about politics.

In "King’s Men," an intelligent, mature narrator describes how a man he never fully trusted betrayed a political trust. In "Colors," a political naivete learns the big lessons of love, honor, betrayal and political expedience.

But in "Hurrah," there is no spirit guide or single voice to lead the reader. O’Connor serves as omniscient narrator, popping in and out of all the characters’ heads. There’s no tell-all character with which a reader can empathize. The reader has to pick his or her own favorites, as no one character is endowed exclusively with the narrative thought or voice.

The result is a book that makes one think and imagine, as the reader must constantly weigh gradations of evil while reassessing one’s own place in such equations. Philosophical considerations aside, O’Connor’s lack of a central narrator makes it necessary for all the characters to work harder to fill the void. In other words, there’s lots of character development and interesting side stories throughout "Hurrah."

Here’s how Skeffington picks them up and puts them down as he plans his next campaign:

"We can count him out, then, if all he’s got is Camaratatta," Skeffington said. "And while we’re at it, let’s count Camaratatta out, too. For good. I’m tired of him. He’s a double-crosser we’ve put up with for years just because he controlled that longshoreman vote. I’ve never liked him personally, but more important, I don’t think he’s as strong as he used to be…I say it’s high time we froze him out permanently…Any objections?"

People still do and say those things, but in few modern novels are such arguments advanced with the candid eloquence O'Connor brings to "Hurrah." There’s little breast-beating, little solicitude, guilt or consideration of morality in those words. Instead, Skeffington and all the characters go full tilt, without the restraining hand or paraphrasing voice of a singular narrating character.

Skeffington’s story is as old as that of any cave-dwelling strongman who used guile and strength to win predominance over his fellow rockers.

It’s not too hard to imagine Skeffington and his myrmidons as medieval condottiere clad in hose and doublets and hatching plans for urban ascendancy against the backdrop of an umber bell tower in Renaissance Italy. And echoes of Skeffington’s appreciation of naked political power are heard in quarters as mundane as a back room in the city motor pool, during an argument over who gets to drive the municipal mosquito control truck, ride shotgun, or sit in the middle.

But one reason why "Hurrah" is no longer heard or read is because it’s dated. That, unfortunately, is made clear early on in the book, during the same conversation cited above, as Skeffington and his cronies discuss and dissect yet another mayoral candidate, a young challenger who owns a string of hair salons.

"A barber for dames," Weinberg said. "He fixes their hair in a couple of beauty shops he owns...Strictly a nut kid, Good-looking, wavy hair, melty eyes, about twenty-nine or thirty. He goes over big with the old dames."

"Too bad it’s an election instead of a beauty contest," Skeffington said. "I’m afraid J.J. is in for a disillusioning experience."

In this age in which style trumps substance and function often follows form, those words mark Skeffington and the gang as badly-out-of-touch losers.

With that passage, the story is mired in time, and unfolds as a particularly eloquent story of hubris and high office in a time far removed from our own.

Hence, the book’s fading from public consciousness. "Hurrah" deserves a better fate.

James M. Abraham is a syndicated book columnist.

He can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com (copy and paste only. No direct link)

Edwin O’Connor’s "The Last Hurrah" is the fast-moving, well-textured story of the last mayoral campaign of city boss J. Frank Skeffington.

But "Hurrah," written in 1956, is a forgotten book today. More folks probably remember the movie of the same title, which starred Spencer Tracy and adhered well to the book. That’s too bad because "Hurrah" is probably the most well- developed political novel ever written. In our time it can be compared more than favorably with Joe Klein’s "Primary Colors," the popular book by a magazine writer about a rising political star from Arkansas.

"Hurrah" takes us from the political novel standard set by poet-laureate Robert Penn Warren’s gloomy "All the King’s Men" to "Colors."

But of that trinity of twentieth century American political novels, "Hurrah" is the most underrated. Here’s why, even as many celebrate or hibernate in the days following the presidential election, readers should consider picking up a copy of the book for a not-so-distant reflection of politics in an earlier time. And here’s what separates "Hurrah" from the two better-known novels about politics.

In "King’s Men," an intelligent, mature narrator describes how a man he never fully trusted betrayed a political trust. In "Colors," a political naivete learns the big lessons of love, honor, betrayal and political expedience.

But in "Hurrah," there is no spirit guide or single voice to lead the reader. O’Connor serves as omniscient narrator, popping in and out of all the characters’ heads. There’s no tell-all character with which a reader can empathize. The reader has to pick his or her own favorites, as no one character is endowed exclusively with the narrative thought or voice.

The result is a book that makes one think and imagine, as the reader must constantly weigh gradations of evil while reassessing one’s own place in such equations. Philosophical considerations aside, O’Connor’s lack of a central narrator makes it necessary for all the characters to work harder to fill the void. In other words, there’s lots of character development and interesting side stories throughout "Hurrah."

Here’s how Skeffington picks them up and puts them down as he plans his next campaign:

"We can count him out, then, if all he’s got is Camaratatta," Skeffington said. "And while we’re at it, let’s count Camaratatta out, too. For good. I’m tired of him. He’s a double-crosser we’ve put up with for years just because he controlled that longshoreman vote. I’ve never liked him personally, but more important, I don’t think he’s as strong as he used to be…I say it’s high time we froze him out permanently…Any objections?"

People still do and say those things, but in few modern novels are such arguments advanced with the candid eloquence O'Connor brings to "Hurrah." There’s little breast-beating, little solicitude, guilt or consideration of morality in those words. Instead, Skeffington and all the characters go full tilt, without the restraining hand or paraphrasing voice of a singular narrating character.

Skeffington’s story is as old as that of any cave-dwelling strongman who used guile and strength to win predominance over his fellow rockers.

It’s not too hard to imagine Skeffington and his myrmidons as medieval condottiere clad in hose and doublets and hatching plans for urban ascendancy against the backdrop of an umber bell tower in Renaissance Italy. And echoes of Skeffington’s appreciation of naked political power are heard in quarters as mundane as a back room in the city motor pool, during an argument over who gets to drive the municipal mosquito control truck, ride shotgun, or sit in the middle.

But one reason why "Hurrah" is no longer heard or read is because it’s dated. That, unfortunately, is made clear early on in the book, during the same conversation cited above, as Skeffington and his cronies discuss and dissect yet another mayoral candidate, a young challenger who owns a string of hair salons.

"A barber for dames," Weinberg said. "He fixes their hair in a couple of beauty shops he owns...Strictly a nut kid, Good-looking, wavy hair, melty eyes, about twenty-nine or thirty. He goes over big with the old dames."

"Too bad it’s an election instead of a beauty contest," Skeffington said. "I’m afraid J.J. is in for a disillusioning experience."

In this age in which style trumps substance and function often follows form, those words mark Skeffington and the gang as badly-out-of-touch losers.

With that passage, the story is mired in time, and unfolds as a particularly eloquent story of hubris and high office in a time far removed from our own.

Hence, the book’s fading from public consciousness. "Hurrah" deserves a better fate.

James M. Abraham is a syndicated book columnist.

He can be reached at jabrajot@hotmail.com (copy and paste only. No direct link)

Saturday, November 06, 2004

Essay-The Big Five-Oh

The Big Five-Oh

by L H Harrell

There's something bothersome about entering the sixth decade of my life.Born and raised in south Florida where retirees outnumber nativesthree-to-one, I've never considered 50 as OLD, but I do consider it theadvent of respectable middle-age. There's the rub. How can I have reachedmiddle-age when I feel so unfinished? Not "unfinished" as in hopes andwishes unrealized. It's more actual than that. More like raw lumber -- Ifeel like an unfinished plank. Unpainted, unvarnished, unmilled, I may yetbecome clapboard or carpenter's lace, bookshelves or barn siding.

I used to envy those who decided early on what they wanted to be; the oneswith definite goals and gumption enough to reach them. In my own meanderingcourse, I've met many career professionals in mid-life crises who wereconvinced they'd taken a wrong track. Apparently, shaping your skills to fityour goals does not create an ideal existence. Perhaps shaping your goals tofit your skills is more fulfilling. I always thought so, along the lines of"do what you love and the money will follow." But I've learned that simplydoing what you love is not always enough. To build a career doing what youlove takes constant practice and even more, it takes determination.

When I was young I thought I had a goal, but all I really had was a littletalent and a big dream. It took just one scornful college professor to determe. He made it clear that, in terms of finished furniture, I was manydrawers shy of a desk and (in his opinion) had no business aspiring to beone. I failed the course. It was my major. Having lost my pride, myconfidence and my tuition-paid scholarship, I dropped out.

Thirty years ago, I thought he'd ruined my life. Now, I think he did me afavor. Had he not bulldozed my dream, I would have spent a few years tampingthat little talent into his "proper" formats and a lifetime wondering why.Instead, I've spent all these years doing what he said I couldn't do, honingthat talent into a skill I'm told is of sometimes formidable force. I'mstill not a desk, but as a strong plank with few knotholes I'm a lot closerto it than if I'd been pruned as a hedge. Some say I achieved my goalanyway. They're wrong. Many a contract has been signed on a plank with acouple of saw horses under it. That doesn't make it a desk.

Now that I've turned 50, I'm no longer comfortable with the philosophy ofachievement I adopted when my dream-goal took a dive, basically, "Lordwillin' and the creek don't rise." If the Lord weren't "willin'," I wouldn'tstill be hacking away in self-imposed apprenticeship. When the creek rises(as it always does), plain old planks are mighty handy for getting to highground. Something else I learned along the way - on high ground, lost dreamscan reappear. A bit of sanding, a little polish, and they shine up good asnew. Give me another 50 years - I might yet make a roll top.###

Award-winning essayist L.A. Harrell flunked Freshman English 101 (BasicComposition). She now earns her living as a freelance writer/publicist whodreams of writing novels.#####

by L H Harrell

There's something bothersome about entering the sixth decade of my life.Born and raised in south Florida where retirees outnumber nativesthree-to-one, I've never considered 50 as OLD, but I do consider it theadvent of respectable middle-age. There's the rub. How can I have reachedmiddle-age when I feel so unfinished? Not "unfinished" as in hopes andwishes unrealized. It's more actual than that. More like raw lumber -- Ifeel like an unfinished plank. Unpainted, unvarnished, unmilled, I may yetbecome clapboard or carpenter's lace, bookshelves or barn siding.

I used to envy those who decided early on what they wanted to be; the oneswith definite goals and gumption enough to reach them. In my own meanderingcourse, I've met many career professionals in mid-life crises who wereconvinced they'd taken a wrong track. Apparently, shaping your skills to fityour goals does not create an ideal existence. Perhaps shaping your goals tofit your skills is more fulfilling. I always thought so, along the lines of"do what you love and the money will follow." But I've learned that simplydoing what you love is not always enough. To build a career doing what youlove takes constant practice and even more, it takes determination.

When I was young I thought I had a goal, but all I really had was a littletalent and a big dream. It took just one scornful college professor to determe. He made it clear that, in terms of finished furniture, I was manydrawers shy of a desk and (in his opinion) had no business aspiring to beone. I failed the course. It was my major. Having lost my pride, myconfidence and my tuition-paid scholarship, I dropped out.

Thirty years ago, I thought he'd ruined my life. Now, I think he did me afavor. Had he not bulldozed my dream, I would have spent a few years tampingthat little talent into his "proper" formats and a lifetime wondering why.Instead, I've spent all these years doing what he said I couldn't do, honingthat talent into a skill I'm told is of sometimes formidable force. I'mstill not a desk, but as a strong plank with few knotholes I'm a lot closerto it than if I'd been pruned as a hedge. Some say I achieved my goalanyway. They're wrong. Many a contract has been signed on a plank with acouple of saw horses under it. That doesn't make it a desk.

Now that I've turned 50, I'm no longer comfortable with the philosophy ofachievement I adopted when my dream-goal took a dive, basically, "Lordwillin' and the creek don't rise." If the Lord weren't "willin'," I wouldn'tstill be hacking away in self-imposed apprenticeship. When the creek rises(as it always does), plain old planks are mighty handy for getting to highground. Something else I learned along the way - on high ground, lost dreamscan reappear. A bit of sanding, a little polish, and they shine up good asnew. Give me another 50 years - I might yet make a roll top.###

Award-winning essayist L.A. Harrell flunked Freshman English 101 (BasicComposition). She now earns her living as a freelance writer/publicist whodreams of writing novels.#####

Essay-Cooking Spaghetti for my writing class

Cooking spaghetti for my writing class

>

>By Henry Burt Stevens

>

>Young children usually like spaghetti and my kids ate lots of it. When they were 4, 7 and 10 years old I was working at home and often involved in cooking supper. The way we tested to see if the spaghetti was done was to fish a piece out of the pot and fling it up against the ceiling. If it stuck it was done. If it came back down, we cooked it some more and tested again, with plenty of laughs. After a while my wife Pat taught us all how to test spaghetti in a couth manner.

>

>Testing one's writing can be handled the same way. Submit, and if it is rejected, send it out again. Be pragmatic, not sensitive.

>

>Where aspiring writers mingle, the first question among strangers often is, "Have you published?" When I'm asked, my answer is yes, and if they say they have not published my question is always, "Where have you been submitting?" I'm amazed when the answer is they've never sent anything out.

>

>I encourage every writer to send material out on submission. Obtain the requirements of the venue and send it. One time I heard a writer boast they had just received their 1,000th rejection in the mail. But, they had also received 257 letters of acceptance.

>

>If your submission is rejected it does not necessarily mean your writing is unworthy. It might merely mean the venue you sent it to can not use it on the day they looked at it. Send it somewhere else, quickly.

>

>Recently I won first prize in a poetry contest. I do not want to embarrass the judges, but the poems had previously been rejected by Crazyhorse, Atlanta Review, Amelia Magazine and the Florida Review. While none of these venues could use my poems, The Brown Pelican Press, across the Peace River waters in Port Charlotte, did find the material useful.

>

>Did the poems improve by riding around the United States Postal System? No. They improved by being offered in a venue that could use them. Dreaming about being published will not get you published. But a program of regular submissions will. Somewhere, someone will appreciate and use your work. Keep on flinging it out there - eventually, something will stick!

>

>###

Reprinted from Oct 2003 edition of Writing Currents, with their kind permission. henry

>

>By Henry Burt Stevens

>

>Young children usually like spaghetti and my kids ate lots of it. When they were 4, 7 and 10 years old I was working at home and often involved in cooking supper. The way we tested to see if the spaghetti was done was to fish a piece out of the pot and fling it up against the ceiling. If it stuck it was done. If it came back down, we cooked it some more and tested again, with plenty of laughs. After a while my wife Pat taught us all how to test spaghetti in a couth manner.

>

>Testing one's writing can be handled the same way. Submit, and if it is rejected, send it out again. Be pragmatic, not sensitive.

>

>Where aspiring writers mingle, the first question among strangers often is, "Have you published?" When I'm asked, my answer is yes, and if they say they have not published my question is always, "Where have you been submitting?" I'm amazed when the answer is they've never sent anything out.

>

>I encourage every writer to send material out on submission. Obtain the requirements of the venue and send it. One time I heard a writer boast they had just received their 1,000th rejection in the mail. But, they had also received 257 letters of acceptance.

>

>If your submission is rejected it does not necessarily mean your writing is unworthy. It might merely mean the venue you sent it to can not use it on the day they looked at it. Send it somewhere else, quickly.

>

>Recently I won first prize in a poetry contest. I do not want to embarrass the judges, but the poems had previously been rejected by Crazyhorse, Atlanta Review, Amelia Magazine and the Florida Review. While none of these venues could use my poems, The Brown Pelican Press, across the Peace River waters in Port Charlotte, did find the material useful.

>

>Did the poems improve by riding around the United States Postal System? No. They improved by being offered in a venue that could use them. Dreaming about being published will not get you published. But a program of regular submissions will. Somewhere, someone will appreciate and use your work. Keep on flinging it out there - eventually, something will stick!

>

>###

Reprinted from Oct 2003 edition of Writing Currents, with their kind permission. henry

Wednesday, November 03, 2004

About Vico Press by henry

Vico Press is the chronicle of Henry wanting to find out if any of his poems are good enough to be published. Most all hobby writers harbor this question. Emily Dickinson was a notable exception, hiding her life's output in a trunk in the attic.

But the rest of us would like to find out how to see our material published.

While trying to answer this question for myself I discovered there is a well worn path to being published. First, get a MFA from as prestigious school as you can afford. Second, submit to small presses and poetry contests until you build up a list of published poems. With this behind you seek a grant. Someone has to pay the bills. Meanwhile, start putting feelers out

to the many publishers who do publish poetry books.

to the many publishers who do publish poetry books.

I do not have time for all this. Also, I've found that if one wants different results than everyone else, one should do things a different way. ("and that has made all the difference") The germ for Vico Press was I felt that a support community could be developed which would help us all.

You are invited to join in this effort. Vico Press is currently printing Henry's chapbooks, which he self published. Vico Press will sell other self published works. Vico Press will feature weekly column writers. Vico Press will also publish many, many guest articles, reviews and writing confessionals.

Taken as a whole there should be information of help to everyone.

Won't you join in?....................thanks, henry

Tuesday, November 02, 2004

Here is my shipment that goes FEDEX tomorrow morning to Orlando Hilton for the Florida Writers' Association, FWA., annual conference bookstore. I have my little display, 20 copies of the chapbook "Victory" and 20 copies of the chapbook "Destruction." Of course I wonder what will come of this????...bye for now, henry